-

An analysis by the Debt Observatory in Globalisation looks at the global situation of supply and value chains of the so-called “clean technologies”

-

Despite the efforts to re-industrialise by the USA and the EU with plans such as the Inflation Reduction Act or the Green Deal Industrial Plan, Made in China continues at the forefront

-

In turn, Global South countries continue to be the main suppliers of critical raw materials and centralising the impacts of so-called green extractivism

-

You can get a free copy sent home. Fill in the form.

The pandemic, and, most importantly, the war in Ukraine have accelerated a technology-based green and digital transition aimed at substituting a fossil fuel based energy mix to one made up of renewables.

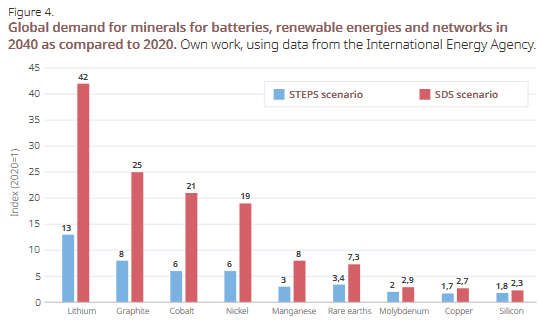

This technological bid for the “green transition” represents an imperative for states to expand the mining frontier, boost industrialisation and secure markets for the sale of technological products. Hence, the most relevant international actors are using numerous instruments, laws, and treaties to gain hegemony on the international chessboard in order to extract minerals and produce and sell technology.

The fact is that China continues to hold a dominant position in the green industry arena, with a hegemonic presence at different stages of the supply chain. For instance, it controls 87 % of materials’ processing operations of rare earth elements, necessary for wind turbines, traction motors, heat bombs or electrolysers.

The USA and the EU follow after China, in an effort to re-industrialise and in constant competition for the factory.

It isn’t lithium mining, it is water mining

Zero emissions in the Global North, externalisation of impacts to the South

Most of the reserves of minerals needed for the green transition are naturally located in countries of the Global South, such as the Democratic Republic of Congo, Mozambique, Peru, Ghana, Indonesia, Chile, Argentina, Bolivia and Brazil. Their extraction is already generating environmental, social and gender impacts on their populations, and the projection of future demand suggests that these will only increase.

“It isn’t lithium mining, it is water mining”, says Francisco Mondaca, member of Association or irrigators and farmers of Toconao, nearby Sant Pedro de Atacama (Chile). Yet, the impact on water is not the only one in extraction areas: pollution, economic dependence and even gender-based violence are part of everyday life. Julieta Carrizo, resident in Fiambalá (Argentina), declares that “in the village bar, on Saturdays it is full of mine workers who harass, impose their economic power and persecute women, many of whom are minors”.

These voices are the result of the field work carried by the ODG team in extraction areas in Chile and Argentina in November 2022.

In the context of the current climate emergency, it is necessary to accelerate the transition, but it must be done by accelerating, at the same time, the reduction of demand by the countries of the Global North, defining a framework of “indispensable extraction” that draws some material limits for a transition taking into account environmental, social and global justice. At the same time, it is necessary to promote an industrial sector of urban or secondary mining that recovers minerals for the manufacture of technologies and contributes to the drastic reduction of primary demand.

It is also necessary to speed up a fair transition to distribute the work, reduce the polluting productive sectors, especially the production of superfluous goods and services, and redistribute the care work that is mostly carried out by women and, in particular, by migrant women.

Any green transition must be globally just. For this reason it is essential to establish processes for canceling the external debt of Global South countries and determine if some debt can be considering illegitimate, e.g. through citizen audits, taking into account also the ecological, climate and historical debt that the Global North owes to to global South.

And finally, in times of climate emergency, the transition has to be financed through a fair tax system, for example through a permanent tax on extraordinary benefits and high incomes. This collection of taxes should be aimed at mitigating the impacts of the transition especially on the vulnerable population.