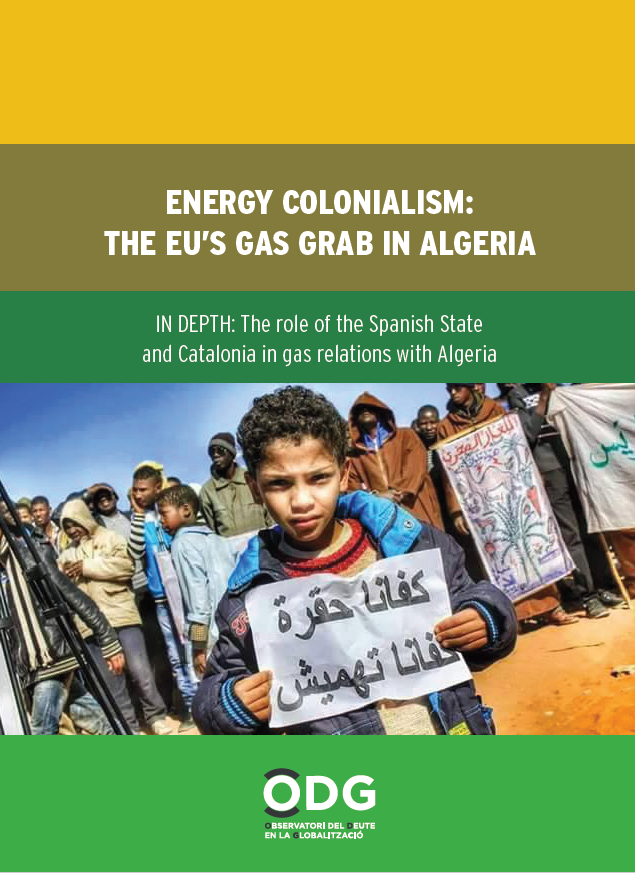

During the first five months of 2015, Algeria witnessed an anti-fracking uprising. The people of the Algerian oil and gas-rich Sahara, in their tens of thousands, rose against the authorities and multinationals’ plans to frack for shale gas in the country. This uprising needs to be situated in its correct context, a context of political and economic exclusion; and the plundering of resources to the benefit of a corrupt elite and the predatory multinationals, ready to sacrifice human rights and whole ecosystems in order to accumulate profits.

Already in the 1990s, BP, Total and Arco signed multi-billion dollar contracts in Algeria, only a few years after the military coup in 1992 that cancelled the first multi-party legislative elections in Algeria since independence from French colonial rule. In November 1996 a new pipeline supplying gas to the EU was opened, the Maghreb-Europe Gas Pipeline, running through Spain and Portugal. These contracts were signed while a brutal civil war was raging, with systematic violence from both the state and Islamist fundamentalists.

These contracts have framed the EU’s engagement with Algeria over the past 20 years and continue to shape the current context of impunity, repression and corruption. The eagerness to break into Algeria in the 1990s, despite the violent crackdown being enacted by the state, indicates the priorities of the EU. The EU and its multinationals favoured their own economic interests and acquiesced to the Algerian regime’s ‘Dirty War’. The same approach has continued ever since.

The EU considers Algeria to be a strategic partner because of its oil and gas resources. With North Sea gas reserves dwindling dramatically and with the Ukrainian crisis, guaranteed access to Algerian gas has been identified as an economic and strategic priority for the EU, explaining why the country features heavily in EU energy policy.

This energy policy aims to lock North African natural gas into the European grid and is heavily influenced by arms and fossil fuel interests. As a result, The European Commission is promoting a

‘diplomatic energy action plan’ to diversify the EU’s natural gas supply sources, with plans for tapping Algeria’s huge unexploited reserves, and a comprehensive Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) strategy due next year (2016). This is a euphemism for the EU’s aggressive attempts to grab more Algerian gas (be it conventional or unconventional) while ignoring the Algerian people’s will and, in the case of shale gas, grievances and concerns for their water and environment.

Today, Algeria is ruled by an ageing regime and a frail president, clinging on to power and lashing out at those demanding democracy and challenging corruption. Yet EU governments continue to ignore the social movements and civil society, instead courting the Algerian regime.

This report argues that the EU External Energy Policy is prioritising corporate fossil fuel interests and a locking-in of Algerian gas over human rights and people’s sovereignty.

Authors:

Hamza Hamouchene

Alfons Pérez